“A white car with a red cross was sent from the Austrian embassy in the fall of 1956. It was an opportunity to go to the west if we so desired. However my grandfather had such a strong cultural definiteness (Hungarian Reformed) that our staying was not a question.” - said Éva Szacsvay, the granddaughter of László Ravasz, the former Bishop of the Danubian Reformed Church District. We asked her about the church leader’s value system, historical role, grandparental love and legacy.

In the Family Circle

“In the mornings we slipped into his bed, where he read us Goethe and Schiller or recited poems of Petőfi and Arany by heart.” - recollected Éva Szacsvay her dearest childhood experiences. She also learned to read at the foot of her grandfather, sitting under his desk: showing him the book she had just picked up, asking about the letters. His extended family living out in the countryside also inherited his love for literature. “His library of four-thousand books was always available for me: philosophy, history, history of art, theology, the whole Hungarian and European literature and works of cultural anthropology. I couldn’t even comprehend then what a blessing this was.” - said Éva. She owes her interest in ethnography to her uncle, István Bibó and László Ravasz, her grandfather always had his eyes and hands on them. He also helped Éva with everything, whether it was her career choice or an improvised church marriage in the room of their flat in Bimbó Street.

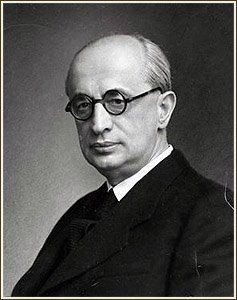

László Ravasz was born in the Transylvanian Bánffyhunyad on 29th of September, 1882. In the Theological Seminary of Cluj (Kolozsvár) he was the secretary of the Bishop György Bartók, and the head pastor in the Romanian region. Between 1907 and 1921 he was a professor in the Theological Seminary of Cluj. In 1918 he was elected as the Vice Bishop of the Transylvanian Reformed Church District, then in 1921 he became the Bishop of the Danubian Reformed Church District. In Budapest he served in the Reformed congregation of Kálvin tér, until he resigned due to the pressure of the communist dictatorship, and returned to Leányfalu. His wife was Margit Bartók, the daughter of the Bishop György Bartók, with whom he had five children. He died in Leányfalu on 6th of August, 1975.

Their grandparent - grandchildren relationship was much more: László Ravasz supported the whole family in a spiritual sense, wherein his cheerful nature also helped him out. “We were the evil bourgeois, the incompetent good-for-nothings. We could survive those times only so, as he always saw the humor in situations. He made everyday shine.” The family lover and respected bishop was tortured by power, it was the most painful for him when his family members were taken and jailed one after the other. Éva’s father was in the hospital for a long time. They visited him in the prison of Székesfehérvár too, where they hugged him in his striped pyjama.

Instead of relocation, László Ravasz was given the “allowance” by Rákosi (head of the Hungarian Communisty Party), that if he resigns from all of his position and retires as a pastor, he can move to Leányfalu. He was ready to do all of this with one condition: his daughters would move home with him from Okány. They needed to dessert a civic lifestyle of Budapest for a more rural one in the countryside, and they could only do that if they stuck together. While on the porch of an extinct civic era, László Ravasz spent his decades of solitary with creative work. He was constantly reading, making notes, translating the Bible and he could sometimes even preach, so long as it was approved by the State Office for Religious Affairs. He also led Bible studies for small communities from Budapest.

He took a position as a elder in the Reformed congregation of Pócsmegyer, and had a good relationship with Sándor Borzsák, the pastor, who tried to involve him more closely in the life of the community. Every week he led Sunday school for the children and his grandchildren, and in the lack of chocolate he rewarded them with sugar cubes covered with ampelopsis leaves. “This meant a little compensation for losing the post as a congregational leader and preacher, that he missed so much. Although he was never physically tortured, and because of his international reputation he was not sued with a show trial, he lived the most painful way of exile, because the thing that he knew and loved doing the most was taken from him.” - explained Éva.

A Reformed Voice in the Time of Revolution

The 23rd of October is the anniversary of the 1956 uprising in Budapest against the Soviet regime in Hungary. It began as a student-led demonstration, which marched through the streets of Budapest to the Parliament building. As they marched, students announced a list of 16 demands for the government. Violence broke out on the streets when demonstrators were fired upon by the State Security Police outside the radio building. A short lived revolution spread throughout the country that was ultimately unsuccessful when the Russians again stormed the country on 4 November.

Pastor Above All

To the question of which values she has got from her grandfather, Éva lists: awareness and education, love for literature, honour of work and learning, diligence, task orientation and resistance. The Transylvanian culture, acquaintanceship and experiences, that transylvanianess, which you could only comply with hard work. “My grandfather held proper guidance and teaching as the most important tool in everything, in the work and in faith. He never forced anything, but let his faith show itself naturally. He believed that everyone is an individual and should find their own place in the world.”

Like she says, the former church leader considered his strong, intimate, complete and unquestionable reformed faith as a gift of Christ. He was deeply interested in the congregational faith, at the same time however he saw, that a religiosity was going downhill in the villages. She added, he felt that this world was of unique spirituality, and that the “folk theology” should be preserved. In 1915 in the magazine called “Az Út” (The Way) - which was founded by her grandfather- called on the rural pastors to deal with the spirit of the congregation, to make an archive about their everyday life. From this evolved the strong Reformed ethnographic researches of the thirties: with the works of Géza Kiss in Kákics, Lajos Fülep in Zengővárkony and Kámán Újszászy in Sárospatak.

“Primarily he thought of himself as preacher, his fundamental principle was Christian ethics, which leads to the good solutions.” Although his work as a church leader is yet uncovered, she thinks that László Ravasz was up-to-date, and a considerable, deciding leader who used his outreach skills exceptionally well - being able to make connections easily. László Ravasz, who had reformed pastors in his faily, was protestant in the first place, and Reformed within. After he moved with his family from Transylvania, he tried to adapt to the new situation and become more open. “It’s proven, that he asked the Lutheran bishop, Béla Kapi and his wife to be the grandparents of his youngest child.” - mentioned Eva.

In the Shadow of Trianon

László Ravasz posed as an important bridge between Transylvania and the mother country not only in the aspect of church, but culture. He tried to use his skills, in the best way, to solve the national tragedies. He had to balance between the German and communist pushes, while he saw the misery of his nation. As a representative of the Upper House of the Hungarian Parliament he presented a new successional bill for the easement of the peasants who were ruined after the abolition of serfdom, but it was rejected. “He wasn’t only speaking, but was trying to do something for the people. His main goal was the reannexation of Transylvania, that succeeded in 1941. This is why he did everything, his willing to help, his worry pushed him for the Hungarian nation.”

“He was voting for the first and the second Jewish Bill also with the intention behind, that we should try as long as we can to remain by the German’s side in order to become one country again. While the first two bills were a strong legal mutilation, by the third it became clear to him what was really happening. To this he firmly said no and not only helped save the Jews, but if it’s not him, then the whole mission is unsuccessful.” - stated Éva Szacsvay. The granddaughter also points out the fact that he supported the baptism of the Jews, but he went further than the formalities: he wanted the escapers to become real Christians. “How could the viewpoint of a reformed pastor be any different as they are the ones who evangelized for the people about Christ?”

“Although retrospectively he judged himself so: he made the wrong decision, the process wasn’t evident yet.” - believes Éva. “We couldn’t even comprehend how the people and the leaders experienced Trianon (Treaty after the WWI) at that time. Instead of the dates and dry facts we should try to understand that historical milieu, wherein decisions had to be made.” - she explained. In her opinion the whole society was greatly shattered by the pain of Trianon, that until this day we could not really process. This is why she thinks it’s extremely important to make investigations about lifestyle and milieu, microhistorical researches in order to have a more layered exploration of the past.

A Hungarian Reformed

The personality of László Ravasz meant a willingness to fight for the family in the aspects of both morality and ethics. He didn’t put his Reformed faith above everything else, but thought of being a Hungarian Reformed as a life determining cultural heritage. A cornerstone for this identity was patriotism, that he couldn’t settle for a quiet and successful future abroad, even when this opportunity was handed to him on a plate. “Being a Hungarian Reformed meant a profession for life, an obligation and a responsibility for him: responsibility for the congregation, for the church, for the town and for the whole Hungarian nation.” - stated Éva.

His main role was the service as pastor. The preaching and the spiritual guiding of the people was his main mission. The commitments and the faith in Christ both characterised his life. “How he lived, that was being a Reformed itself, he wanted to do good for the people. Only for few people is given such a talent, and maybe even he wouldn’t be able to make such an achievement in a more peaceful century. I am grateful to be his granddaughter, I couldn’t imagine a better man and grandfather.”

Éva Szacsvay was born on 5th of May, 1945, as a child of Éva Ravasz, the youngest daughter of László Ravasz, and of Dr. Ferenc Szacsvay, the former vice notary of Cluj. After finishing the degrees of ethnology and Hungarian literature in ELTE (Eötvös Loránd University), she worked in the Museum of Ethnography, where she has done numerous research projects in the field of folk religiousness. The ethnographer has made the comprehensive European-level, bilingual catalogues titled Üvegképek (1996) and Szobrok (2009). The 25-year-long permanent exhibition after the system change is also due to her. Her research on the Catholic culture in Mezőkövesd, the Transylvanian Reformed culture in Kalotaszeg, the collections of Moldva, and the 20-year-long examination of the life of the small Reformed community of Dunabogdány is expecially notable. She researched first and foremost the mentality, the changings of life-style and the history of the related objects in connection to that. In this topic several of her publications and articles were published.

Written by Orsolya Szoták

Originally published by Parokia.hu

Translated by Tímea Tőke

Edited by Avery Gill

Photo: Vargosz

From Revolutionist to Bishop

In rememberance of the Revolution, RCH talkes with Rev Zoltán Szűcs whose lifestory is very much connected to the events of 1956.

For Freedom and Truth

Minister of State István Bibó, a reformed-calvinist lawyer and political scientist, addressed a proclamation to the nation and the world, defending the revolution and the nation that had conducted it, on 4 November 1956.