Maria Kojdecka came to Budapest from Warsaw as a volunteer with no real plan of where she would work. All she knew was that she wanted to teach and wanted an adventure. Within the first few weeks of arriving in Budapest, she found herself at the community center of the Reformed Church in Hungary’s Refugee Ministry.

“I kept wandering around the place repeating like a broken record, ‘I’m an English teacher. I could teach English….’” Finally, it was decided: she would teach English in the center’s Tanoda (after school) program. However, Maria soon realized that all the teaching preparation she had learned in Poland simply did not apply.

“The first case was very challenging. There was a boy who left Afghanistan when he was about 17 or 16. He managed to get to Europe but he was homeless for two years, so he did not attend any school…(Tanoda) registered him at some school, but obviously people who are 17, they don’t learn the alphabet or numbers.”

In the beginning, Maria was frustrated that he did not seem to be putting forth effort in their lessons, but it finally struck her that maybe he simply did not understand. “So we started learning letters. I played him that song – you know A, B, C, D. He was 20 at that point, so he started laughing, but I told him, ‘Don’t think about it. Don’t feel embarrassed.’”

According to Maria, an individual approach is necessary with each student. "You can’t use any newspapers, because they just don’t understand the people, they don’t really watch Western movies.” Beyond this, the teaching structures that students in Europe learn from the very beginning – workbooks, exercises, reading a text and discussing – the refugee students simply do not know or understand those patterns.

“That’s the point. When you learn to be a teacher in English studies, they teach you how to teach adults and children of your own origin. They teach you some fixed methods. And, they just don’t work when you go to another country, when you teach people from another culture.”

It was a good lesson for Maria as well. She had no simple solution to the challenge of teaching. Instead, it was a process that required teacher and student to use all the skills they possessed to reach a common ground. Sometimes this required a mixture of English and Hungarian, online translators, whatever they had, to understand.

“We grew on each other. They started trusting me. They saw that I was putting effort into those lessons.” This is one reason it was so difficult to leave after volunteering for only three months. “I was really devastated I had to go, because at the end of those three months, something had clicked and I finally knew how to do it.”

So, after returning home to Warsaw and a regular office job, Maria still felt connected to Refugee Ministry in Budapest. In fact, she came back to the city for several weeks of her summer holiday in 2014 to reconnect with her old students and to teach again.

“It’s not only about learning new things, learning the language. When you’re an outsider, it’s always difficult. Even when you’re Polish in Hungary, it’s not that easy to make friends, and we don’t have a different skin color … I think that those social workers and those teachers, they understand it. They understand that need.”

But, how does she move forward from this? Well, she has shifted her focus to working with refugees, investigating opportunities at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and teaching programs for refugees through Polish NGOs.

“You start thinking from that viewpoint: what if it was me who had to flee? … Anyone’s life can be at risk, any one of us can be forced to flee. It’s a good thing that there are organizations like (the Refugee Ministry). There are a lot of things to do in this area still.”

Amy Lester

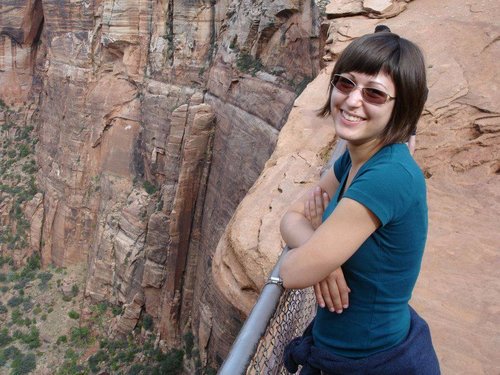

Photo: Maria Kojdecka